DollarStore

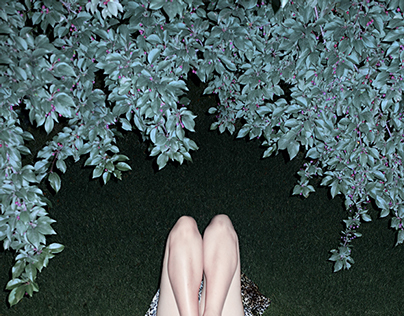

"Sir, if you have purchased this product, please would you be so kind as to send this letter to the World Organization for Human Rights. Thousands of people who are being persecuted by the Chinese Communist Party will thank you and will remember forever. " - Message from a worker in the Masanjia Labor Camp, Shenyang, China, 2012. If, according to Guy Debord, the carnival-like spectacle that characterises the second half of the 20th century "is not a set of images, but a social relation among people, mediated through images" (The Society of the Spectacle, 1967), never more than today (and less than tomorrow) social relationships between producers of cheap goods and Western consumers would have been so severely unbalanced. While gigatons of disposable objects, devoid of any practical or even aesthetic value, are exposed in one dollar stores - equally available to the derision of the rich and the use of the poor - it is no longer possible to ignore the indecent conditions linked to the production of these objects by Asian mega-factories. Recent history is full of tragic examples of plants where these worthless objects are made and whose retail cost per unit has absolutely nothing in common with the value of the lives regularly lost in the manufacturing chain. I applied myself to magnify to the extreme the aesthetic potential of these $1 plastic trinkets, rendering them aggressively kitsch, in order to show the absurdity of their existence, with the hope - perhaps illusory - of generating a reflection, or even to transform consumers’ attitudes about them, and also to act in a practical way to transform the working conditions of the makers of these very vulgar objects. In this perspective, I extend my practice centered around the sublimation of the banal, already begun in other series (Alternative and experimental landscape, Stranger Project, On the beach, Undernight, etc...). Within Dollarstore however, the object acquires a new and crucial importance. I approach the subject in a quasi-sculptural way, manipulating and transforming it physically before taking a picture. Once photographed, the object and its environment will not be retouched. In the final phase of the project, I try to answer the call for help issued by a Chinese worker in Shenyang, which a consumer from Oregon found in the packaging of their Halloween decorations. I intend to infiltrate myself in the mass consumption circuit by printing my photos into postcards that I will distribute in one dollar stores, unbeknownst to the customers who will find them, in turn, in their purchases. By acting through the media of the image, I hope to provoke a questioning of the value of the objects when placed in relation to their conditions of production, and thus link the image to its concrete reality. In a kind of anti-show, at once beautiful and grating, these images are subverted and try to become a riposte at the "heart of the unreality of the real society," these photographs that are overly kitsch, like the show itself, "the sun that never sets over the empire of modern passivity” (Debord, 1967).